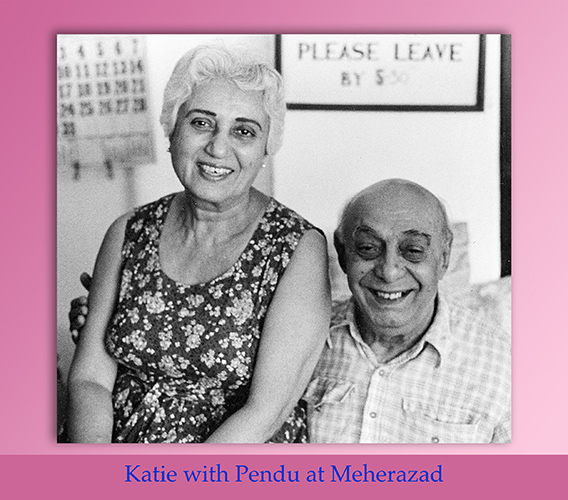

Katie Irani Women Disciple and Mandali of Meher Baba – Meherabad

Meherazad

Avatar Meher Baba’s dearest Katie Irani flew into her Beloved’s arms on 29/05/09 at 0410. She passed away from heart failure in Meherazad; she was 89 years old. The cremation was held at 1730 on 29/05/09 at Meherabad. Katie’s ashes are interred by the east side of His Samadhi on Meherabad Hill.

Falling For Baba

[Posted on 29.08.2009]

Several years ago, before Katie’s health took a serious downward turn, she was sitting on Mehera’s verandah with just a couple of us ‘girls’ listening to her reminisce about her life with Meher Baba.

Katie was a marvelous storyteller, and that day she had us all in stitches laughing so hard that it hurt. She paused for a moment before beginning another story and said, “You know, if ever I were to write a book about my life with Meher Baba, I think I would call it, ‘Falling for Baba.'”

Unfortunately, her enthusiasm only lasted a short while. The demands of the kitchen called, and her energy for such a project ebbed quickly. Whenever the idea of the book was brought up, she would brush it aside. Her mood had completely changed. But not before we had recorded some of the wonderful stories that she shared that quiet afternoon.

With Katie’s passing on 29th May 2009 so close in memory, our thoughts continue to focus on the unique role she played in her life with Meher Baba: a life lived for Him both in the ashram and in the world. A life carved out of the poignancy of separation, molded and sculpted by the demands of obedience and surrender to His Pleasure, and then polished by the necessity to find humor and joy in the most mundane frailties of our human existence.

I met Katie for the first time in 1978, when she retired from the Japanese Consulate in Bombay and came to Meherazad to stay. At that time, Katie told me a sweet story about her connection to Baba that I have never forgotten.

Baba was visiting her parents and in conversation He innocently asked her mother, “So, how many children do you have?”

Her mother replied, “Why, Baba, I have seven children.”

“No,” came Baba’s prompt reply. “You have five children. Two of your children are mine.”

No one understood the meaning of Baba’s cryptic statement, especially Katie’s mother. But years later when both Katie and Goher left home to live with Meher Baba, in spite of their mother’s dismay, it became undeniably clear; Baba had known from the beginning that these two children were His and His alone.

Katie Rustom Irani first met Baba when He came to her home in Quetta, India, in 1922, and from her childhood she felt drawn to Him. Although she was part of the women’s ashram in Meherabad, and traveled with Baba on the Blue Bus, she was ordered by Baba before He left for the New Life in 1949, to go to Bombay, live with Nariman and Arnavaz Dadachanji, and take up a job.

As Katie recalled:

On 15th October, when Baba disbanded the women’s ashram the Hill, He dispersed all the women mandali to different places. I was sent to Bombay, a place which I never liked in all my life. I remember thinking to myself, oh my God, the worst place I could ever be in. But I had to say, “Yes, Baba.” Finished. I could never refuse Baba anything, and so I was sent to Bombay.

Then Baba said, “You are not just to sit at home and do nothing.” And that is how I ended up at the Japanese Consulate.

When Baba sent us off, He told us, “You will never see Me again. You will not have any contact with Me and you will not write to My companions or have any connection with them. I am sending you all away, but you are still under My wing and so I am there with you always. But you will never see Me again.”

We were in the East Room and when Baba made that announcement, I said to myself, how is it possible? Baba will see us sometime.

Baba turned His head sharply in my direction and said, “Believe Me one hundred percent that you will never see Me again. Don’t cry, be happy.”

I looked at Baba and I just said, “Yes, Baba.” Do you know what it was like? Here I had spent eleven or twelve years with Baba in His constant companionship and then He tells me, “Don’t think you will ever see Me again.”

The whole way to Bombay I thought, this is a bad dream. It can’t be true. I am not going to Bombay·until I climbed the steps to Arnavaz’s doorway. But something happened when I came to Bombay and deep down I don’t know why it was, but I kept on falling; whether it was some deep down separation from Baba that aggravated me into this falling all the time, I don’t know. Thank God, Baba saved me, as every time I fell, I did not break any bones. But I had some extraordinary falls.

In 1952, Baba came to Bombay and He used to enjoy hearing my stories of falling down all the time. So one day, He was standing by the door and He asked me, “Katie, why do you fall down all the time?”

“I don’t know, Baba.”

“Next time you fall, send Me a telegram.”

I said, “Yes Baba.”

I have never said no to Baba in all my life. But in my mind, my stupid mind, I’m thinking, I work for the Japanese Consulate and these people won’t let me out of their sight for five minutes. To send a telegram I would have to catch a bus, go to the telegraph office, wait in the queue, because there was always a serpentine queue at the office, all to send a telegram to Baba. And then I would have to catch a bus back to the consulate. It would take me at least two hours. How will I escape?

And you know, Baba looked at me and said, “No, no. I don’t think a telegram will work. You know what? Every time you fall, just remember to say, Goodbye Baba. Say it loudly so I will hear you in Meherazad and I will know Katie has fallen down.”

“Thank you Baba. Yes, Baba.”

“You will remember? Make sure, every time you fall, just say it loudly, and I will hear you in Meherazad.”

I used to save all my leave to be with Baba. I never took leave for anything else. I didn’t want to fall sick, as they would deduct that from my leave. We had no special sick leave, only twenty days in a year. That was all. But, because I was the personal secretary to the Consul General, they wouldn’t let me go. At the most they would give me four days. And every time I wanted to take leave, they would give me such a fight.

I said, “Sir, you give people twenty days at a time and you won’t give me four days? I am tired. I also need leave.” So I would have to mix the red letter days – the official holidays – with my four days to make seven days. Then I would take the night train. Right from the office I’d rush to the station, buy my ticket and sit all night on the bedding rolls on the floor, reach Ahmednagar and take a tonga (a horse drawn carriage) to Meherazad so that I wouldn’t waste my time traveling. It was not an easy life, I tell you. It was hard work, but I put my heart and soul in my work.

When I came for my holidays to be with Baba, the first thing He would ask me when I entered the room was, “Did you fall?”

“Yes, Baba.”

“Where? Tell me.”

You know about the monsoons in Bombay, how awful they can be, just like buckets being thrown down on you. It just pours and pours like mad. So one day I was attending the office in the morning and it was just pouring rain. I had taken my raincoat and cape with me, but I was just holding it in my lap as I sat in the bus. When we approached the stop closest to my office, I thought to myself I better put the raincoat on so I won’t get drenched. I stood up to put my cape on and at that moment the bus driver suddenly put on the brakes. My two feet flew up in the air; “Good bye Baba,” I called out as my purse and lunch bag went flying, leaving me sprawled out in the dirty water that had collected in the aisle, while everyone on the bus looked at me. Just then, my stop came and I had to get off the bus. So people started helping me up. You know, my fruit had fallen out of the bag. I had brought a banana for my lunch and it just went splat. The apple went rolling down the aisle and everything spilled out. Someone picked up the apple and said to me, “Madame is this yours?” I felt so embarrassed. I reached the office and went straight to the bathroom and just stood under the shower.

Baba and Mehera laughed so much when they heard this story. But every time I’d fall, people would laugh and laugh. I would be lying on the floor and nobody would help me because they were laughing so hard.

Then one day I got down from the train platform and had to walk through a bazaar. I was meeting my brother there. As I stepped out and headed into the market place, I didn’t see a green chili. I knew when I went through the market that I had to be very careful as they would throw out lots of rotten vegetables and the place was strewn with them, so I knew I had to mind all that, but as I stepped down I didn’t see this small green chili which was squashed and slimy. My foot stepped on it and I skidded in front of all the vegetable vendors. Right in the middle of that market I was sprawled out! Chee·And who is standing there watching it all but my brother Jal. He is just staring at me saying, “Poor dear, you’ve fallen.” And I said to him, “Forget about it and come pick me up! Can’t you give me a hand?”

Katie told story after story that afternoon, regaling us with accounts of falls in her office, falls on the roadside, falls in Ashiana, Arnavaz and Nariman Dadachanji’s residence, and every other imaginable place. But what gave one pause, behind the laughter her humorous misadventures elicited, was her resignation to the wish of her beloved Baba. It mattered little whether His pleasure was to send her to live in dreaded and detested Bombay during the New Life, or for her to remember to call out “Goodbye Baba” whenever she fell, or even for Baba to return in 1952 and shatter all hope of being part of the ashram again, by ordering her to remain in Bombay. What mattered was only that she always said, “Yes, Baba.” And this Katie did till the very end.

But all those falls she endured during her lifetime could not have prepared her for what Beloved Baba destined to unfold in the last seven weeks of her life.

It is one thing to experience the momentary humiliation of having to rely on others to help oneself up from a fall; it is an entirely different matter to be made totally dependent on others to see to every mundane daily life chore. Katie found herself bound by a condition that gradually made it impossible for her to move; it robbed her of the ability to turn over in bed, sit up, stretch a leg or even scratch a mosquito bite on her cheek. Walking was an impossibility as was washing her face or feeding herself and, eventually, swallowing. But even this unbelievable limitation and restriction in movement was nothing in comparison to the loss of speech that she experienced. She, who had sung to her Lord with the voice of a nightingale, found her voice gone; in its place was a whisper that we could barely understand. For those of us trying to give her comfort and care, it was truly heartbreaking, for as much as we were willing to do anything to alleviate her pain, it became impossible to know what it was she needed from us. Baba had placed His Katie in an impenetrable prison and He alone held the key to her release.

Yet, for those of us who were blessed to care for her during these last months of her life, her humor, wit, courage and gracious acceptance of what Baba was giving her, never ceased to amaze and inspire us. In spite of her utter physical helplessness, and our utter feelings of helplessness to assuage her suffering, it was she who reminded us, “Why are you sorry I am suffering? It is what He wants.”

Even in our clumsy attempts to serve her, she would shed humor on the moment by raising an eyebrow at our imperfect endeavors, or laugh with us, even when she didn’t have the energy to talk, as we witnessed her belly shaking up and down with sheer joy and abandon at the joke someone had cracked when we thought she was asleep.

Yes, we shall miss our dear Katie, but we find joy in her release. No more “Good-bye Baba” for Katie; it is we, who stand here now saying, Goodbye, Katie.

Davana Brown

For Tavern Talk

29 June 2009

Click for next page:>>