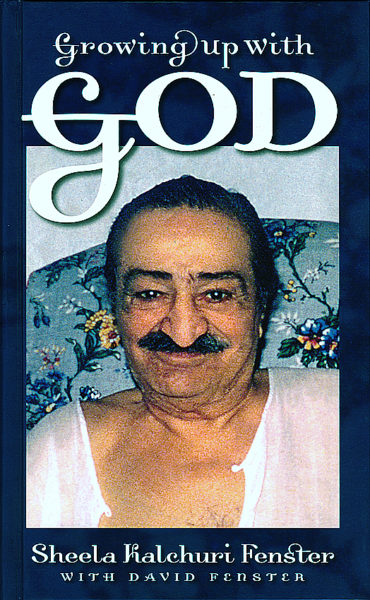

Growing up with God by Kalchuri Sheela

Sheela’s father Bhau Kalchuri joined Meher Baba as one of the mandali in 1953. Four years later, Baba called Sheela and her family to live in his near proximity. The Kalchuris had many opportunities to be in the Beloved’s presence, and Sheela’s first-person account paints a vivid, intimate portrait of life near Meher Baba, from the perspective of a child and teenager.

Sheela’s father Bhau Kalchuri joined Meher Baba as one of the mandali in 1953. Four years later, Baba called Sheela and her family to live in his near proximity. The Kalchuris had many opportunities to be in the Beloved’s presence, and Sheela’s first-person account paints a vivid, intimate portrait of life near Meher Baba, from the perspective of a child and teenager.

New Book by Sheela Kalchuri Fenster

Growing Up With God chronicles a unique time spent in the company of Avatar Meher Baba by a precocious young woman who first met Baba when she was less than one year old. Sheela Kalchuri Fenster lived in Meher Baba’s physical proximity for twelve years, from the time she was five until Meher Baba dropped His body in 1969, when she was 17.

People often wonder what it was like to live near Meher Baba and Growing Up With God gives a candid look at life behind the scenes with both the men and women Mandali. It is a tale rich in lessons for us all, demonstrating the enormous amount of suffering and sacrifices required to live near the Avatar of the Age.

How to Order:

Buy Now From Meher Baba Books

Buy Now from Amazon (Kindle edition)

Buy Now Meher Nazar Books

REVIEW OF THE BOOK GROWING UP WITH GOD BY KENDRA

In this lively memoir, Bhau Kalchuri’s daughter, Sheela, tells her story with the help of her husband, David Fenster, who edited transcripts of her recollections given over many years. This has been a labor of love for both of them, and we must applaud the Fensters for sharing so many inspiring and intriguing glimpses of Meher Baba as well as the men and women who surrounded him. Accompanying the text are 146 photos (half of them in color), most of which are being published for the first time.

Born in 1952, Sheela first met Meher Baba when she was less than a year old, and she lived in close proximity to him from the age of five until Baba dropped his body in 1969, when she was seventeen. She was aware from her earliest years of the sacrifice her family had made in order for her father to serve Baba as one of his close mandali. When she was older, Sheela told Baba, “A rose surrounded by thorns is like God’s beauty – we have to undergo suffering to reach Him.” Baba replied: “True, but when you are near me, I pluck off the thorns, so you don’t get hurt.” Sheela has had her share of suffering. As a youngster she suffered a terrible, painful accident, with severe burns on her back and arms from boiling milk. She almost died of typhoid and from a serious mastoid infection; Baba told her he had saved her from death several times.

Sheela’s parents, Bhau and Rama, both came from wealthy Hindu families and lived in comfort in Nagpur prior to setting aside their lives of privilege for the inestimable blessing of being with Baba. Bhau initially had no interest in spirituality and was pursuing three simultaneous graduate degrees; but a couple of powerful dreams, an unexpected experience at the tomb of the Perfect Master Tajuddin Baba, and a single meeting with Meher Baba transformed him. With the agreement of his pregnant 21-year-old wife, Rama, Bhau left his young family right after his graduation in 1953 to join Meher Baba. Sheela was not yet two years old; her brother, Mehernath, was born a few months later.

Rama then raised her children alone, although with the loving guidance and support of the Avatar of the Age. Bhau was ordered to give up his attachment to his family, although Baba also required him to write regularly to Rama (a number of these letters, containing news, advice, and occasional admonishments, are included in the book). Baba praised Rama for not complaining about being separated from her husband. (In addition, she accepted living in reduced circumstances compared with her upbringing as the daughter of a raja.) Baba has to remind Bhau of the extraordinary nature of his wife’s sacrifice: “You have no idea about her. No woman in the world would live like her, all alone there with two small children. She is really good.”

After a few years Baba called Rama from her parents’ home to come with the children and live near him. They arrived at Meherabad around April 1957 and moved into a bungalow near Arangaon village. Sheela describes her frequent visits to Meherazad, where she witnessed the qualities and quirks of the mandali, as well as precious times with Baba at Guruprasad in Pune. In 1963 the family moved to Khushru Quarters in Ahmednagar, the site of the present Trust Compound, which in those days was a private residence for Adi K. Irani’s family as well as the location of the Ahmednagar Baba center.

Sheela recalls that Baba never referred to her and her brother as Bhau’s children, but always called them the mandali’s children. “Don’t ever say they are Bhau’s children,” Baba declared. “They do not belong to him. They are my family.” At other times, Baba would tell her, “Who is Mani? My sister, you think? I don’t have any sister; I don’t have any brothers. I don’t have a mother or father. … God doesn’t have any relatives. God has only lovers.” A recurring undercurrent in the book is a kind of tension between attachment and detachment in relation to family. Sheela reports that she has always felt that Baba was her true parent. Yet her sense of family is strong as well. Although she did not have much contact with her father while growing up, since he was always busy serving Meher Baba, she loved him dearly.

If anyone ever wondered whether God really cares about the thoughts and feelings of one little pigtailed girl, Sheela is here to lay that doubt to rest. A remarkably bright child—outgoing, talkative, and bold—“Baby” (as Baba and her family called Sheela) would ask Baba outrageous questions, and get answers to them: How can we tell if someone is from another planet? Why doesn’t Baba either make everyone in the world good or kill off the bad people? Why did God have to create ugly creatures? Would Baba please give her some powers so she can fix things that are wrong with the world? Why can’t he make her win the lottery? (Baba’s reply: “Never do that. So many people buy tickets and all their sanskaras go into that. The person who wins thinks he has won lakhs of rupees, but in reality he gets lakhs of sanskaras.”)

If her imperious manner as a child drew complaints from the mandali, Baba defended her, saying that her sanskaras were those of a wealthy, sophisticated person—a princess. “Baby was supposed to be born in a royal family,” Baba explained, “but in order to be near me, I’ve given her birth in this family.” He also said she was supposed to have been born a man—and Bhau was supposed to have been a woman! Baba admitted he had made a mistake in assigning their genders.

Baby’s best childhood friend was Dr. William Donkin. William, as she called him, taught her the English alphabet, fixed her hair in a cute way, impressed her with his artistic talent, and explained to her how to love Baba: “Never demand anything from Baba. Accept what he tells you and follow his orders accordingly. If he wants you to live like this [on little money], accept it. Never ask Baba for anything.” Sheela took such lessons to heart and had an instinct for loving the Beloved: “Because Baba would sometimes pat my head or remark that my brain was sharp and tap me on the head, I never wore hairpins or clips in my hair when I went to Meherazad. Baba might get hurt when I embraced him or when he put his hand on my head. So I braided my hair into two braids to keep it in place. Mehera asked me once in front of Baba why my hairstyle looked old-fashioned. I explained why I had not used any clips, and she was pleased.”

Sheela was allowed to help Bhau with the Hindi correspondence and could not resist adding her own advice directed at any writers whose letters to Baba had annoyed her—but Baba always found out and made her cross out her contribution to the reply. Mehera let Sheela file Baba’s fingernails and comb his hair. She was fortunate to spend hours alone with Baba at Guruprasad, sometimes massaging him. And she received various orders from Baba, including one in which she had to shout insults at the mandali. Baba gives her tips for how to spend Silence Day, deals with assorted encounters with ghosts, and assigns her a special short daily prayer meant for her alone.

We are treated to glimpses of many of those who were closest to Baba—in addition to Mehera, Mani, and other women mandali, she writes of Eruch, Dr. Donkin, Padri, Pendu, Vishnu, Chhagan Master, Feram Workingboxwala, Dr. Deshmukh, Nana Kher, Mohammed the Mast, and especially Bhauji himself. The weaknesses of some of the mandali do not escape young Sheela’s observant and discriminating nature. Padri never laughed, and Mansari gave terrible fashion advice. We see the mandali fighting over sweets—and even worse behavior. But Sheela’s insights into the love between Baba and his closest disciple, Mehera, are surely worth the price of admission. The book concludes with a powerful account of Meher Baba’s death and entombment.

I can only hint at the amazing range of details revealed by Sheela. I bet you didn’t know that Baba read palms and facial features, for example; he even interpreted the meaning of a mole on Sheela’s foot! Some of the details are deeply significant, while others are entertaining or amusing: for example, when at Guruprasad, Aloba slept with Pegu the Siamese cat, who he believed would protect him from ghosts. One of my favorites among the touching anecdotes: When Baba was driven to the Arangaon tuberculosis sanatorium to see the patients, he also visited a room where white rabbits were used for tuberculosis testing, and “Baba fed a few pieces of grass to each of the bunnies through their cages.”

Growing Up with God would make an excellent candidate for reading aloud and discussion in a group. There are plenty of surprises in store. And I am sure Sheela will find herself more in demand as a speaker at Baba events after this publication.

http://kendrasnotebook.blogspot.com/2009/05/book-review-growing-up-with-god.html